Introduction

Like so many of my generation, my first exposure to practical music-making was in junior school at the hands of a short, fiery spinster named, with stunning nominative determinism, Miss Fear. Those of us whose parents had scrimped to shell out for one turned up carrying a heavy Bakelite recorder each with a faux-ivory mouthpiece, and to this day I can still remember the first three songs from page one of the manual in its pale-green cover: ‘Pease Pudding Hot’ followed by ‘I Love Little Pussy’ segueing into ‘The Cuckoo’. I haven’t picked up a recorder in over fifty years, but thanks to Miss Fear’s irresistible teaching technique, and muscle memory being what it is, I bet I could still play them note-perfect if you asked me:

G, G-A B; C, C-C, B; G, G-A-B B B, A-A G.

B-C B, A A G-B, B D A A D; B-C B, A A G-B, B D A, A-B G.

D-B, D-B, A G A G. A A B C A, B B C D B. D B, D B, C B A G.

And don’t get me started on The Turtle Drum (“a children’s play for television with music by Malcolm Arnold and words by Ian Serraillier”):

The brave seahorses ride over the swell

(With a something ending deep.

And they do this thing which might end well)

Then bravely on they sweep.

And they greet Kaisu (sp?)

While pearl-eyed foals (‘foals’, you see, because they’re young seahorses)

From their parents’ pouches peep (even at the time I recognised this was alliteration long before I knew what to call it).

Oh stay with us.

Oh sleep with us (I think it was sleep. It might have been eat, less iffy. My wife remembers it might have been Abide)

In Princess Something’s palace.

Crunch!!

At which point all the runty kids down in the percussion section whose parents couldn’t afford recorders were finally allowed to cut loose on the tatty school-supplied instruments, smashing their tambourines and banging their bongos while all the bogeys and the nits and the flakes of ringworm piled up in deep shameful layers around their shabbily-shod feet…

With adult hindsight now I suspect that although Miss Fear tried her best to live up to her name, she didn’t really have the sand, but by the time I realised this it was too late to rekindle my latent interest in the subject, and I miss now not picking up more technical knowledge while I had the chance. I never really learnt how to read music, and when I got to grammar school I was doomed to be put off for good by the abrasive nature of the music teacher there. (Yes, the curriculum included such fripperies as music lessons back then. We even did Latin up to O-Level, for Christ’s sake! I got 74% thanks, how about you?) In our very first week this bastard accused me of speaking out of turn in class – it wasn’t me, it was my mate Zed sitting next to me whispering what a prick he was – but so confident was this guy in the integrity of his pitch-perfect hearing that he shouted down my indignant denials and dragooned me into the school choir by way of punishment. Any joy I might have taken in learning about the glories of the international repertoire were killed off at that moment until I once again found myself free to make my own rapturous discoveries under the sympathetic guidance of knowledgeable and enthusiastic friends. But this wasn’t until much later, at university.

Other early influences were closer to home. My dad had a modest collection of classical records, which included – or may simply have consisted solely of – Holst’s The Planets and Grieg’s Peer Gynt alongside, I think, some Ray Conniff and a Black and White Minstrel Show. We also had a piano that my dad could get a tune out of, a jet-black upright, glistening and sharp-cornered, and I like to pretend that I missed out on learning to play simply because it was in the coldest room in the house – the front parlour, in fact, before we knocked through – and I couldn’t bear to practise for long. Then around my mid-teens I got a hankering to take up the guitar. Since I looked like a hippy, I thought I might as well try to sound like one. My parents, bless them, had bought me a portable typewriter for my sixteenth birthday. Now, as always taking my ambitions almost as seriously as I took them myself, they bought me a guitar for my seventeenth.

You can learn the basic chords by studying sheet music of your favourite pop songs. You know what they’re meant to sound like so if you keep an ear out it all comes together very quickly. The dots on the lines never meant much to me, but the little box diagrams were easy to follow, and once the fingertips on your left hand had hardened up, you could start to strum along. I learnt two valuable lessons this way: some pop songs have even simpler accompaniments than you’d think (eg ‘Maggie May’, ‘Where Do You Go To, My Lovely?’), and others can be a lot more musically sophisticated than you might imagine (eg, ‘Life on Mars’, ‘Chelsea Morning’). Oh, and John Lennon and Paul McCartney’s accompaniments were always genius, by the way.

Once at university I started performing at college folk clubs and did okay through the simple expedient of only doing really good accessible stuff – Jake Thackray and Fred Wedlock for laughs, Pete Atkin for plangency. I could play Ralph McTell’s ‘Streets of London’ but so could everyone else, so instead I did his ‘Maginot Waltz’ or ‘First Song’ or ‘Let Me Down Easy’ or ‘Grande Affaire’. And eventually I started slipping a few of my own songs into my sets as well. I can’t say I ever strayed very far beyond the key of C, but I told myself it was all about the words with me, and you can’t be good at everything.

When I started writing lyrics for other things, I found my interest in and respect for the craft grew exponentially. I’d always been aware of musicals, but I quickly developed a voracious appetite for the whole (mostly American) songbook. Richard Rodgers probably wrote the most ravishing melodies in a very crowded field – I mean, South Pacific alone contains not only ‘Some Enchanted Evening’ but also ‘Younger Than Springtime’. The Sound of Music is probably one of his dullest scores, in my opinion, but maybe they were both getting old by then. (I agree with what Stephen Sondheim said about his own great mentor, Rodgers’s lyricist Oscar Hammerstein: “Oscar Hammerstein was a man of limited talent and infinite soul whereas Richard Rodgers was a man of infinite talent and limited soul.”) In terms of lyrics Sondheim himself probably takes the crown, but for all round craft and sophistication, in the marrying of wonderful words to marvellous melodies, I reckon my all-time favourite must be Cole Porter. When I have my time again, I intend to be a lyricist. Or a translator. Look at Herbert Kretzmer and Les Misérables. You only need to hit the jackpot once…

Here, BTW, is a list of my all-time Desert Island Discs favourite songs, in no particular order. All of these are, for me, note perfect and could not be improved in any meaningful way: ‘Born to Run’ – Bruce Springsteen; ‘Night and Day’ – Cole Porter; ‘Dancing Master’ – Pete Atkin/Clive James; ‘Someone in a Tree’ – Stephen Sondheim; ‘Hazey Jane I’ – Nick Drake; ‘Dancing Queen’ – Abba; ‘America’ – Bernstein/Sondheim; ‘Beim Schlafengehen’ – Richard Strauss (Jessye Norman/Kurt Masur 1983 version).

(Of course, one could immediately compile a second list, and a third and a fourth and a fifth, which in my case would include at least ‘La Mer’ - Charles Trenet; ‘A Nightingale Sang in Berkeley Square’ - Maschwitz and Sherwin; ‘Who Knows Where the Time Goes’ - Sandy Denny; ‘Luck Be a Lady Tonight’ - Frank Loessor; ‘You Belong to Me’ - Jo Stafford, and so on… but you get the idea.)

And even at this late stage in my life, I am happy to say that my musical journey continues. As a retirement gift to myself a couple of years ago, I bought myself a bass guitar. (They only had it in blue in the shop, I had to wait a few days for them to deliver a crimson version. I asked the sales assistant if I was being shallow. He was very nice about it.) The reason was, ever since I first heard the ground-breaking ‘Yours Is No Disgrace’ on The Yes Album (1971), I had wanted to play along with Chris Squire’s thunderous, driving bass line. I’d worked out the notes long ago, and they were easy. You can play them on the three bottom strings of any guitar with standard tuning. It goes E-E-A-E; A-A-D-A; A-A-D-A-A-E - B! If you’re good at changing chords quickly you can give it an even ballsier sound by playing not just the individual strings, but the full chords that have those names attached (yes, that’s how it works, who knew?), and it sounds great, especially if you can whip up to that meaty B major bar chord on the 7th fret and then slide your whole hand down the fingerboard in what we in the music industry call a ‘glissando which goes downwards’.

So, great excitement the first day I unpacked my bass, and set the CD going (I’m old school all right?). But what’s this? I had got it wrong! Not the notes, of course, they were solid, but the octave. Chris doesn’t play it down there on the bottom E string of his famous grungy Rickenbacker, oh no, he plays it up here, a whole octave higher. He starts on the A string, 7th fret, then goes up to the 4th string, 7th fret! IKR? And that’s not all! Instead of going up again to the D note on the G string, he gets that D by going down to the A string, 5th fret! I’d got the note right, just not the register. And that’s so he can make the most of the glissando which goes downwards from the B on the 6th string, which takes you all the way down into the deepest bowels of the song. Then Tony Kaye starts up on that Hammond organ of his, doesn’t he – they all had them in those days, Keith Emerson, Gary Brooker, Rod Argent – and you sort of busk along with that for a bit, and then there’s that brilliant sequence where you just plunk bottom G for a few bars, like a bear farting down a well, and then Jon Anderson’s glorious choirboy voice comes soaring in, doesn’t it, “Yesterday a morning came, a smile upon your face,” whatever the hell that means, at which point I generally give up because after that it starts getting really complicated.

Probably just as well I didn’t take up the bass to begin with, otherwise none of these songs would ever have got written. Qualis artifex pereo.

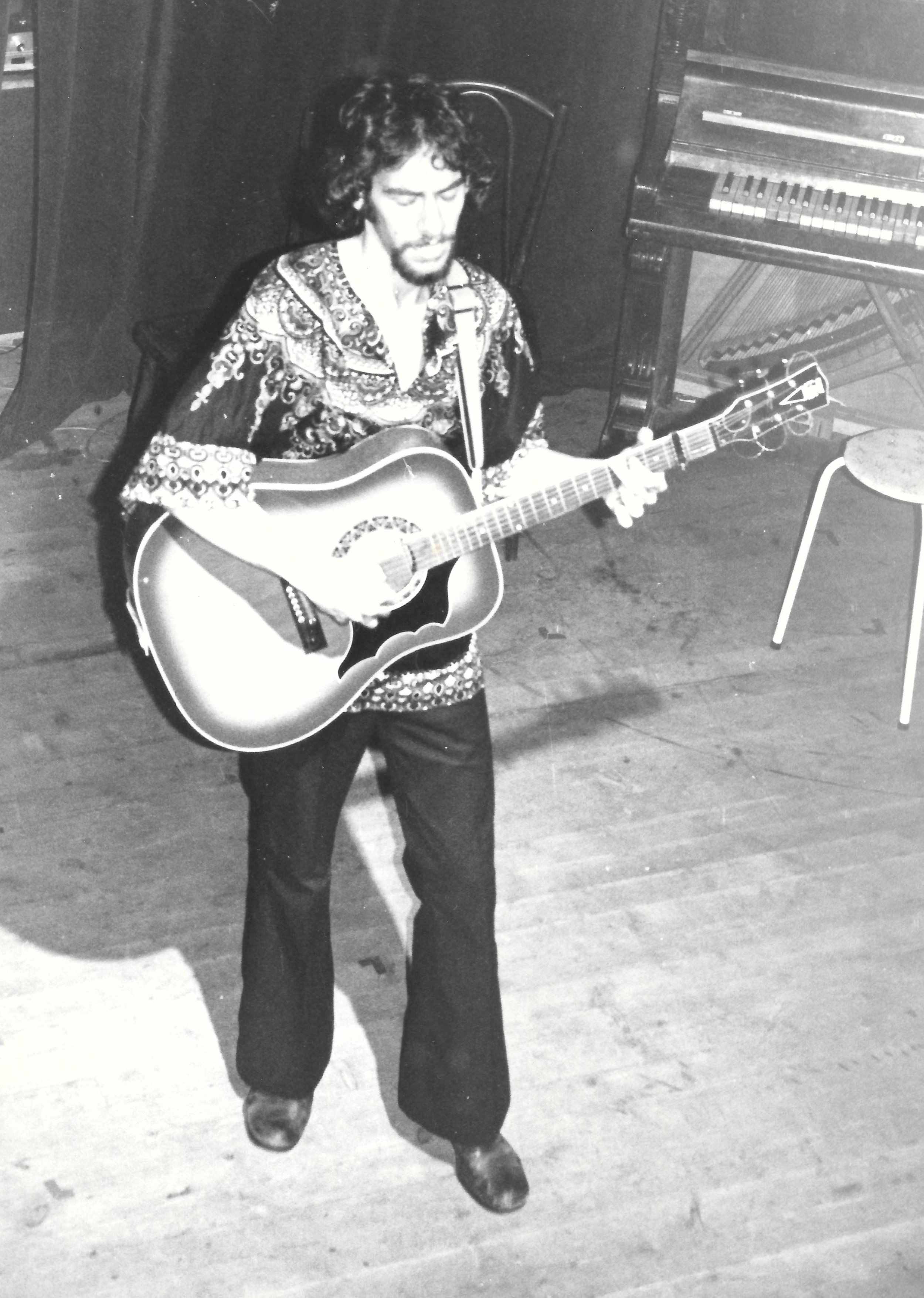

From the cover of my proposed debut album, The Bassist Wore Slippers

Explore

-

Songs

n. musical works which went cheaply